Crime Magazine April 2013

Forensics: The Chocolate Factory Case

April 18, 2013

How bite marks can lead to convictions.

by Liz Porter

Criminals are regularly nabbed because they make stupid and careless mistakes. The burglar who robbed a safe at the up-market Haigh’s chocolate factory in the South Australian capital city of Adelaide is a perfect example. He was caught by his own bad manners. On his way to burgle the establishment’s safe, he toured the factory’s display area, helping himself to samples and biting into several chocolate bars. He then threw the uneaten leftovers on the floor – from where police collected them. If he had taken his uneaten chocolate home – or neatly disposed of it in a rubbish bin – he might never have been caught.

The robbery took place on a weeknight in early February 1996. Office staff arriving for work at the inner suburban factory the next morning discovered that an intruder had broken in through a skylight. He had used an axe and jemmy to bash the alarm system off the wall and had then overturned the office safe, making a hole in its back and removing the $1,800 inside. The workers also spotted the partially eaten chocolate bars the thief had dropped on the floor, and noticed that he had also stolen chocolate from a display area nearby.

Police recovered the uneaten chocolate, noting that clear tooth marks were visible in a 40 by 55-millimetre piece of chocolate frog, a 27 by 29-millimetre portion of chocolate honey nougat, and a 40 by 77-milllimetre bar of plain chocolate.

The chocolate evidence was stored carefully, while police closed in on a man they believed to have been responsible for a recent series of similar night-time break-ins. A gourmet deli had been robbed on January 14, and bus tickets, blank checks, phone cards and $400 worth of cakes were stolen. On January 22, a travel agency had been robbed of foreign currency. Then, a week later, and only three days before the Haigh’s heist, a robber had climbed through a window of another travel agency and stolen $4,850 in cash. Possibly emboldened by his success in previous break-ins, he left a handwritten note for police or, as he called them, the “boys” in the “Beuro”(bureau) telling them they had “better be considering a new line of work,” and signing it “Traffick.”

The police suspected that the person responsible for all these burglaries was a 24-year-old man from the Adelaide suburb of Northfield. When they raided his home, they seized property allegedly taken in the previous cake shop and travel agency robberies. They also took a Valentine’s Day card with the man’s handwriting on it. But their suspect continued to deny involvement in any of the robberies.

Police were able to use their powers under Section 81 of South Australia’s Summary Offences Act to compel the man to have impressions of his teeth taken with special dental gel. These impressions, along with the chocolate samples, were sent to Adelaide University’s Forensic Odontology Unit, where Dr. Kenneth Brown made casts from the impressions of the suspect’s teeth and used the same gel to make casts of the tooth marks in the chocolate surfaces. The casts were then examined and compared and photographed microscopically.

DNA analysis wasn’t considered as an investigative tool in this case. Although DNA profiling was already being used at Adelaide crime scenes by 1996, the technology available at that time wasn’t up to detecting traces on chocolate, and in separating saliva from chocolate. By 1998, new technology was introduced that revolutionized the sensitivity and reliability and speed of DNA analysis. Even if this case were to happen now, the bite-mark examination would still include forensic odontology, which would be used, with DNA, to add weight to the evidence presented in court.

The suspect’s teeth, Brown noted, had certain distinctive features. He had a 1.5-millimetre gap between his upper left central incisor and his lateral incisor. (The central incisors are the two front teeth, top and bottom, while the lateral incisors are the teeth either side of them.) The upper left lateral incisor was rotated at an angle of about 20 degrees off center. There was a recognizable notch on the biting edge of the upper right lateral incisor and noticeable facets of wear on both the upper right central incisor and the lower right lateral incisor.

Types of Bite Marks

Brown’s next task was to examine the kind of bite marks that had been left in the chocolate samples. Broadly speaking, bite marks in foodstuffs vary according to the kind of food being bitten, and have been classified as Types 1, 2 and 3. Type 1, typically seen in chocolate, fractures the foodstuff, but allows only limited tooth penetration, so that the bite marks will only record the most prominent edges of the incisors and some of the characteristics of the outer edges of the upper and lower front teeth. Type 2, typically seen in apples, requires extensive pressure by the teeth, and sufficient penetration to create a fracture of the surface. Type 3, usually seen in cheese, fractures the food surface, but allows complete or near complete penetration by the teeth.

Fortunately for the investigators, the honey nougat bar, with its layer of softer nougat below the chocolate surface, displayed a Type 3 bite mark, retaining marks made by the scraping of the teeth and recording a more detailed impression of the suspect’s upper and lower front teeth. In particular, the notch on the upper right lateral incisor was recorded in the cast made of the bite marks, along with the distinctive facets of wear on the outside biting edge of the suspect’s lower right lateral incisor. In fact, the entire outline and dimensions of the suspect’s tooth was reproduced exactly in the cast taken from the nougat.

The bite marks on the chocolate frog and the chocolate bar provided extra details, but the nougat evidence was the most useful source of corresponding details between the bite marks and the suspect’s teeth.

After seeing Brown’s results, police had enough evidence to charge their 24-year-old suspect. But, in May 1997, when the man faced the Adelaide Magistrate’s Court on six charges of breaking and entering between November 1995 and February 1996, he continued to deny any involvement in the burglaries, pleading not guilty to all charges.

He may well have been cheered by the news that the chocolate samples, having been returned to police custody after Brown had cast the bite marks in them, had significantly deteriorated during Adelaide’s February 1997 heat wave. But while the original chocolates themselves couldn’t be produced, police tendered the casts made of them as evidence, along with the casts of the suspect’s teeth.

Brown told the hearing that the likelihood of two individuals having an identical dental imprint was “so remote that it is difficult for us to comprehend.” The bite marks recorded in all three chocolate samples bore “remarkable similarity” to the accused man’s teeth, the expert said. The accused, he concluded, had bitten into the chocolates.

The police weren’t the only ones impressed by the forensic odontologist’s evidence. After hearing it, the accused changed his plea to guilty. He also pleaded guilty to the robbery of the travel agency where he had left a note, after he realized that a handwriting expert had matched the writing on a Valentine’s Day card he had sent to his girlfriend to the note he had left for police.

The magistrate, displeased that the accused had pleaded guilty only when “the writing was on the wall, so to speak,” sentenced him to two years in prison.

Not All Bite Marks Are Equal

Evidence of bite marks in foodstuffs have been able offer police more certainty than evidence of bite marks on skin, which has resulted in many unsafe and unjust convictions – all based on the false belief that a bite mark was “as identifiable as a fingerprint.”

Chewing gum, for example, has been proven to be a useful medium for the recording of tooth marks. In the world’s first reported case, involving a 1976 murder in the United States city of San Diego, a wad of red cinnamon-flavored chewing gum enabled local homicide detectives to place a suspect at the murder scene and clinch a conviction.

The male victim had been shot and stabbed in his bedroom and there were two suspects, only one of whose fingerprints were found in the room. Impressions of the victim’s and the two suspects’ teeth were taken to compare with a silicon reproduction of the chewing gum found at the scene. Under magnification, it could be seen that the chewing gum had been wedged against the inside surface of the upper and lower incisor (front) teeth of an unknown person.

Comparisons ruled out the victim and the suspect whose fingerprints had been found. The other suspect had an opening drilled in the inside surface of her upper incisor (as access for root canal therapy). There was also a defect – either a missing filling or some decay – on its mesial surface (the side towards the centre of the mouth). These defects were also apparent on the wad of gum. A blood typing test showed that this suspect and the chewing gum user had the same blood group.

The world’s second chewing gum/tooth marks case was reported in South Australia, in May 1990. A local policeman, Detective Constable Geoff Carson, was investigating a burglary at a physiotherapy clinic in the South Australian town of Murray Bridge when he found a wad of pink strawberry-scented chewing gum on the floor. It was in an area of the clinic that was a private dwelling, not a place where a patient could possibly have dropped it. Noticing that it bore distinct tooth mark-like indentations, Carson asked the crime scene examiner to collect the gum. He arranged for it to be stored in the fridge so that it wouldn’t soften before he got it to a forensic expert.

The break-in had been the latest in a spate of burglaries from local houses and businesses, all involving entry via a smashed window and the theft of food. The size of the windows and the kind of food taken suggested that the offender was both young and of a slight stature. Meanwhile, fingerprints found at some of the scenes had been identified as those of a local 15-year-old. The youth was arrested and questioned, but he denied any involvement in any of the robberies, including the physiotherapy clinic break-in. But if the chewing gum were proved to be his, it would show that he had been in an area of the clinic which he could have no legitimate reason for visiting.

Using Section 81 of the South Australian Summary Offences Act, police ordered that impressions of the youth’s teeth be taken by a local dentist, who pressed a special gel around his upper and lower teeth, creating a shape which then set as a mould. In the meantime Carson contacted Dr. Kenneth Brown of Adelaide University’s Forensic Odontology Unit, and sent him the chewing gum and the dentist’s impressions of the suspect’s teeth.

Brown prepared casts of the suspect’s teeth by pouring a dental stone plaster mixture into the impression moulds. When they had set hard, and the impression moulds were removed, these casts represented the shape of the suspect’s upper and lower teeth. Brown then examined the oval-shaped wad of chewing gum, which measured about 29 by 12-millimetres. After photographing both sides of it, he made replicas of the tooth impressions, using a special polyvinyl siloxane mixture. Comparing the teeth on the casts with the impressions on the chewing gum replica, he noted that seven specific features of upper teeth numbers 23, 24, 25, 26 had been reproduced on one side of the chewing gum. The other side of the gum had produced impressions of teeth that corresponded to the lower teeth numbered 34, 35 and 36. There was insufficient detail of teeth 34 and 36 on the chewing gum, but the impression of tooth 35 on its own mirrored six different features of tooth 35 on the cast.

When the youth was confronted with this forensic evidence, he confessed to both the physiotherapy clinic break-in and the other burglaries where he had left his fingerprints.

This case was so remarkable that Malaysian forensic odontologist Dr. Phrabhkaran Nambiar eventually wrote it up for publication in the June 2001 edition of the Journal of Forensic Odonto-Stomatology. Nambiar, who had assisted Professor Brown with the lab work on this case when he was a postgraduate student at Adelaide University, noted that, while some foods were better than others for bite-mark registration, chewing gum was in a class of its own. Chewing gum, for example, is the only “food” which will show the biting surfaces of teeth towards the back of the mouth, providing information not produced when people bite into other kinds of foods.

Bite marks left on surfaces such as food raise a different set of scientific issues. Food has different properties from skin (such as not moving when it is being bitten) and some foods can record better teeth impressions than skin. In the preface to his paper on the Murray Bridge case, Nambiar documented a variety of food bite-mark cases. In one, a lamington (a small sponge cake covered in chocolate) had been bitten into during a night arson attack on a coffee shop in the South Australian town of Mt. Gambier. The offender was convicted on the basis of evidence provided by a computer-generated image of his dental arch. When this image was superimposed over the bite mark in the lamington, it was found to match.

Forensic science academic literature abounds with examples of criminals convicted after leaving bite marks in foods. In one of his many papers on the subject, British expert David Whittaker reported that one of the earliest bite-mark convictions dated back to 1906, when a burglar was convicted after leaving tooth marks in a piece of cheese.

In 1955 the tooth marks left by an alleged rapist in a cucumber helped to secure his conviction, while in 1971 the tooth marks left by a murder suspect in the pastry of a meat pie were also vital in obtaining his conviction.

British forensic dentist Dr. Colin Bamford has also given evidence about bite marks in a series of different inanimate materials, including cheese and apples. He once testified in a murder case involving a bite mark on a Mars Bar, and in a murder and armed robbery case where the defendant had been chewing the plastic butt on a car key and had left tooth marks.

Junk Forensics

The history of cases involving bite marks on skin is not as impressive. In general, there are too many variables involved in the examination of a bite mark on the skin, where the compression factors vary according to the location on the body of the bitten skin. There may also be problems related to the way the bite mark has been recorded. If a bite mark is very fresh, there will be indentations in the skin. If an impression is taken with synthetic silicone rubber material, these impressions may be reproduced. Otherwise, if the expert is relying on photos, he or she is examining two-dimensional images of a three-dimensional construction.

In fact, the history of forensic evidence in U.S. courts is stained with examples of death sentences unjustly imposed as a result of bite-mark evidence given by dentists. Air force veteran and postal worker Ray Krone, for example, spent four years on Arizona’s death row and another seven in prison on a life sentence after being convicted, in two trials, of the 1991 murder of Phoenix cocktail waitress Kim Ancona. Testimony that his teeth matched bite marks on Ancona’s breast and throat was crucial to his first conviction in 1992 – after which he was labeled “The Snaggletooth Killer.” In 1996, his conviction was reversed on appeal, on the basis of the prosecution’s concealment of evidence from Krone’s lawyers. He was re-convicted in 1996, again on bite-mark testimony, despite DNA tests which indicated that blood found on the victim was not his – or hers.

Krone continued to proclaim his innocence. Finally, in April 2002, DNA tests of blood and saliva on his supposed victim implicated a man by then in prison for sexually assaulting and choking a 7-year-old girl. Four days later, Krone was set free.

In 1992, when a 3-year-old girl was found raped and strangled near Brooksville, Mississippi, police arrested Kennedy Brewer, 21. As the victim’s mother’s boyfriend, he was automatically a person of interest. He was also home alone with the victim and his own two children on the night the little girl vanished. The traces of semen found in the child’s body were too small for 1992 DNA techniques to use. But a confident forensic dentist testified that the 19 mysterious marks on the child’s body were bite marks, five of which matched Brewer’s teeth “with reasonable medical certainty.” (A defense expert said they were insect bites, sustained during the two days the child’s body lay undiscovered in the open.)

Brewer was convicted and sent to death row. In May 2002, new DNA tests indicated that two unknown men raped the tiny victim, and a new trial was ordered. Brewer’s conviction was “vacated” and he was moved from death row to pre-trial detention, where he remained until 2007, when he was released, pending a new trial. In the meantime, investigations by the Innocence Project led to the identification of Justin Albert Johnson, one of the original suspects in the crime, as the perpetrator. Johnson subsequently confessed. Finally, in February 2008, charges against Kennedy Brewer were dropped and he was exonerated.

Yet, some skin bite-mark opinions can be delivered with a degree of confidence. Forensic odontologists can certainly give opinions on whether or not a bite mark is self-inflicted. Their opinion in such cases is based on anatomical as well as dental issues. A person cannot, as Melbourne forensic odontologist Dr. Tony Hill points out, bite themselves on the back, or on the genitals. Hill has testified in several rape cases where he has been able to testify that a bite mark is human, not animal, and made by an adult, rather than a child. He has also been able to state that someone else, not the victim, inflicted the bite. But was that person the accused? He has not been able to say.

Forensic odontologists can also use bite marks to exclude certain suspects – as in a case where an alleged biter has a missing front tooth or unusually crowded teeth and the bite mark doesn’t show the same peculiarity. A biter with unusual teeth might also be able to be identified in a “closed” incident where the culprit has to be one of several suspects (and no one else has had access to the victim). In one South Australian case involving allegations of abuse of a baby girl of approximately 20 months of age, experts from Adelaide University’s Forensic Odontology Unit examined the teeth of five suspects and were able to eliminate the chief suspect and three of the others. The fifth one was the culprit, who was convicted.

Hans Van Meegeren – Master Forger

April 22, 2013

Hans van Meegeren

Hans van Meegeren duped a string of wealthy collectors into paying vast sums for fake artwork of the Old Masters. One victim was Reichsmarschall Herman Goering.

by Robert Walsh

When many people are asked to name a selection of truly master criminals they’ll probably come up with the usual suspects: Jack the Ripper, Charles Ponzi, notorious English highwayman Dick Turpin or maybe legendary Australian bushranger Ned Kelly. One name that’s highly unlikely to appear is possibly the greatest (and certainly the boldest) art forger in criminal history, Hans van Meegeren.

Van Meegeren was born in October, 1889 in the Dutch town of Delft, the same town as the equally legendary artist Johannes Vermeer, a 17th century master. Van Meegeren, like any aspiring local artist, was a fan of Vermeer and was keen to become Delft’s other big name in the art world. He succeeded, but in a way that even the most inventive crime fiction writers couldn’t possibly have dreamt up.

It’s fair to say that the art world in general (and the Dutch art scene in particular) wasn’t exactly overwhelmed while Van Meegeren was painting under his own name. The general consensus among Dutch art critics was that he wasn’t nearly as talented as he aspired to be, was technically crude and, creatively speaking, fairly unoriginal. In short, he was generally regarded as a journeyman painter rather than another Vermeer. Like many people possessing a creative temperament and an artist’s ego, Van Meegeren was constantly stung by the criticism (and sometimes outright dismissal) heaped upon him by critics and contemporaries. Eventually he devised an elaborate (and, some would say, slightly crazy) plan to humble his critics, elevating himself to the standing he craved while doing so at their expense.

Initially, his career as an artist had gone well enough. He earned a decent living painting portraits for wealthy European and American socialites, exhibited his work in his native Holland and further afield and early in his career was invited into the HaagseKunstkring (a select Dutch artistic society composed of young, gifted painters and writers). If he had a problem with the Dutch art establishment it was that his talent as a creative, original artist had peakedby the early 1930s and by the mid-1930s his personal and artistic relationships with his peers had almost totally dissolved. This was due to his own increasing bitterness at the Dutch art community not tolerating his increasingly confrontational attitude and not giving him the recognition he felt himself entitled to.

A Grand Plan

His plan to reverse his fortunes was both technically challenging and perversely brilliant. Rather than simply forging copies of classic paintings by famous artists, Van Meegeren opted to create supposedly undiscovered pieces by a variety of Old Masters. Having (so he hoped) comprehensively duped the critics and collectors previously so dismissive of his own works, Van Meegeren then intended to openly admit he was a forger, create havoc in the art world, humiliate his critics and reap the rewards of the resulting publicity. By the strangest route and largely beyond his control he managed exactly that and, ironically for a forger, any painting proved to be a Van Meegeren is nowadays worth a lot more than it would be otherwise.

His first obstacle was purely technical. Even in the 1930s it was possible for any collector to run scientific tests on a suspect painting. If the canvas wasn’t old enough to match the lifespan of the supposed artist, if the chemical composition of the paint was incorrect or if the brushstrokes were obviously made using a different type of brush (Vermeer was well known to use brushes made from badger hair, for example) then a fake could easily be detected. Granted, with advances in forensic and scientific testing since the 1930s (when Van Meegeren was producing his best work and plenty of it) his fakes would never pass inspection today, but in this era he managed to come up with raw materials sufficiently similarto those of the Old Masters he admired so much. Certainly close enough that they easily fooled the critics and collectors he so despised.

Van Meegeren devised an aging process that, by 1930’s standards, made his fakes almost indistinguishable from the real thing. His paint was custom-made by grinding pigments in oil of lilac and then adding just the right amount of phenol formaldehyde resin dissolved in either benzene or turpentine. The resulting paint had all the right characteristics of a genuine 17th century artist’s paint.

Finding canvas that would pass inspection was rather easier. Van Meegeren simply obtained cheap, almost worthless paintings from the same era, removed the original paint and then recycled the blank canvas into forgeries close enough to fool many art critics and collectors. During the 1930s he produced fakes by a variety of distinguished artists, selling them as newly discovered works. His particular masterpiece came in 1936 when he created a fake Vermeer named “The Supper at Emmaus” which Van Meegeren personally regarded as his finest work. It was instantly accepted by many top-level Dutch experts as being the genuine article.

Hans van Meegeren’s most famous dupe, Reichsmarschall Kerman Goering.

Scamming Kerman Goering

One of his better works was “Christ and The Adulteress” which his artistic agent sold to a German art collector in 1942 for the equivalent of $7 million in today’s money. The collector was none other than Reichsmarschall Hermann Goering, commander of the Luftwaffe and one of Adolf Hitler’s most senior colleagues. Goering (himself an avid art collector) had no idea he’d paid so much for a fake and gave it pride of place in his personal gallery at his official residence, Karinhall. Aside from the obvious risks attached to making a fool of one of Nazi Germany’s most senior figures (while also pocketing a huge amount of his money) the decision by Van Meegeren’s agent would have serious consequences for his employer, although eventually his post-war legal problems would provide him with notoriety, celebrity and the public profile that he so desperately craved.

Money was never an issue for van Meegeren. His fakes went unexposed and for increasingly high prices. A rough estimate is that, in total, he pocketed somewhere around $60 million in today’s money from his many forgeries. He owned houses and hotels, moved around Europe freely before the war and relatively freely during it. He was said to have accumulated so much cash that he began hiding jars and boxes around his many homes and that future residents were still finding caches of pre-war Dutch banknotes even well into the 1960s. His desire for recognition far outweighed his admittedly lavish tastes, a desire that probably extended from his childhood and would only grow stronger as time went on. He could easily have exposed himself as a forger and humiliated many of his detractors long before the end of World War II but instead continued turning out fakes, reaping the profits while laughing privately at those experts he had taken for the fools he thought they were. It was with the end of the war (and the liberation of his native Holland) that a certaindeal with a certain German collector reared its ugly head and he was finally forced out into the limelight.

Van Meegeren in the Crosshairs

In May of 1945 van Meegeren was visited at his studio by two military officers representing the Allied Art Commission. The AAC was busily investigating the vast trade in stolen artwork during the Nazi era. The Nazis (when they bothered buying things instead of simply confiscating them) kept meticulous records of their dealings with art vendors. What they’d bought, where they bought it, how much they paid and (bad news for Van Meegeren) who they paid it to were all easily checked, providing an investigator had access to the right paperwork. The AAC investigators certainly did.

The name of Hans van Meegeren appeared on some of those papers in connection with the supposed Vermeer masterpiece “Christ and The Adulteress” as bought in 1942 by one Hermann Goering. For the first time in his long career as a master forger, Hans van Meegeren was now in extremely serious trouble. What made things especially grim was that he was arrested and held for trial as a suspected Nazi collaborator instead of as a forger. In early post-war Holland forgery didn’t carry the death sentence. Collaborating with the Nazis (especially top-level Nazis) very definitely did.

Van Meegeren was now in a highly dangerous and equally surreal situation. In order to prove he wasn’t a collaborator he would have to admit that he’d been selling forgeries for over a decade. If he confessed to being a professional forger he’d certainly draw a jail sentence for what the Dutch then called “falsification.” If he failed to prove that he was a common criminal and that he’d actually had the nerve to take a top-level Nazi for a fool then he’d quite likely be shot as a collaborator. In the years immediately after the war the Dutch were in no mood to show leniency to collaborators which left him with only one option: Cop a plea for being a top-level international forger and take whatever jail sentence the court chose to hand down.

After six weeks in custody, van Meegeren’s sense of self-preservation and desire for public attention finally won through. During yet another interview with Dutch investigators he finally cracked and bluntly told them that he was a forger. He freely admitted selling forgeries for over a decade and that the painting he sold Goering wasn’t a genuine classic from one of Holland’s greatest artists but was really a fake he’d painted himself. The cat was finally out of the bagand Hans van Meegeren was about to become an Old Master of the criminal variety. He’d serve some time, certainly, but he’d avoid the firing squad and still be able to reap the benefits of becoming a celebrity crook after his release. So far, so good, all except for one small problem.

The investigators didn’t believe him.

Van Meegeren’s artistic talent and instinct for fakery had landed him in a cell, possibly with a firing squad waiting for him. He’d come clean about his extensive criminal career and, when he’d finally shown his true colors, the authorities refused to accept his plea that he was only a common criminal, not a traitor to his country. Just to stay alive he’d now have to completely incriminate himself of lesser charges and simply accept whatever mercy the Dutch chose to offer.

Proving He Was a Forger, Not a Collaborator

Van Meegeren made the authorities a startling offer. He would prove his criminal talents by producing yet another faked painting using his standard mimicry, showing beyond doubt that he really was the master forger he claimed to be. His original plan to make himself a star and shame his detractors had come to fruition, granted. But it had come by a route so convoluted and downright bizarre that truth really had become stranger than fiction.

In front of the court he assembled his raw materials and set to work. While the judges, jury, international media, and the Dutch art community witnessed his every brushstroke(no doubt cringing at the mention of the journeyman they’d sent packing before the war). Van Meegeren showed every little trick and detail he’d used to fool so many people into parting with so much of their cash and credibility. Van Meegeren delivered a tour de force performance, proving beyond reasonable doubt that he wasn’t a collaborator, but certainly was one of the all-time great master forgers.

The charges of collaboration were dropped, the Dutch art community was left in a state of huge collective embarrassment and the most the judges were prepared to give van Meegeren was a token one-year sentence for “falsification.” Van Meegeren himself became an international star touted by no less a writer than Irving Wallace as “The man who swindled Goering.”American art lovers especially regarded him as though he was more of a prodigal son than a career criminal.

Postscript

Sadly for van Meegeren, his fame has long outlived him. While waiting to start his token jail sentence his health (which had been slipping for years through heavy smoking, heavier drinking and an addiction to morphine-based sleeping pills) finally gave out. He succumbed to a severe attack of angina the day before he was due for transfer to a Dutch jail. He lingered for a few weeks, but the damage was done and he died without serving so much as a day of his sentence.

Hans van Meegeren’s fame has survived through his surviving paintings and his legacy as one of the masters of forgery. Ironically, for a master forger, his known fakes and pieces painted under his own name are now worth considerable sums – some have netted six-figure prices, such is the art world’s appetite for his work. Not because they are artistically brilliant, but simply because there are many collectors prepared to pay decent prices to have either a fake Old Master or a genuine van Meegeren in their collections, something which would certainly have been immensely gratifying to him. He set out to achieve fame and fortune and he did so, albeit by so bizarre a route that even he must probably have shaken his head at the sheer strangeness of it all.

Is the Suffolk Strangler Still at Large?

April, 25, 2013

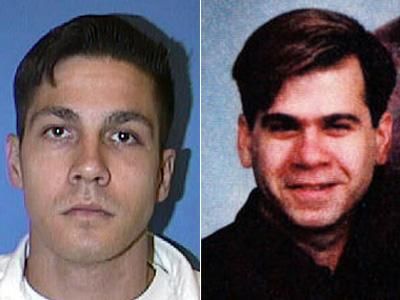

Steve Wright

The murders of five prostitutes by the Suffolk Strangler in 2006 set off one of the largest manhunts in British history. DNA evidence led to the arrest and conviction of a man who admitted he had sex with four of the five dead women, but was he the actual serial killer?

During November and December of 2006, five prostitutes were murdered one at a time in Ipswich, England. Although each was asphyxiated and not strangled, the British media dubbed the serial killer “the Suffolk Strangler.”

Forensic evidence suggested that all five victims were attacked from behind and that the assailant put his arm across the victims’ throats to render them unconscious. The first two bodies were found fully or partially clothed in a nearby river in Ipswich. The last three victims were left naked in woodlands near the same area; no attempt had been made to hide or bury the bodies. Each victim was arranged in the form of a crucifix with her hair extended outwards in the form of a halo. Jewelry and other trinkets were taken from the victims but have never been recovered.

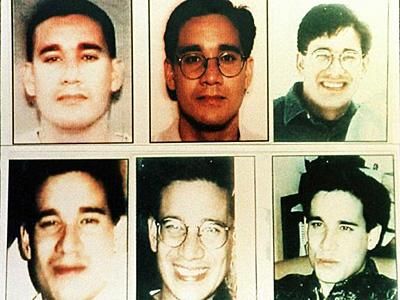

The victims were 19-year-old Tania Nicol, 25-year-old Gemma Adams, 24-year-old Anneli Alderton, 29-year-old Annette Nichols, and 24-year-old Paula Clennell. Clennell, the fifth and final victim, had predicted her own murder during a television interview about the serial killer. She had been friends with the other victims as they worked the same streets touting for passing trade.

At the time of the murders, Suffolk police asked the Forensic Science Service to assist in one of the largest murder manhunts in British history. From the time Tania Nicol was reported missing on November 1, 2006, the police investigation involved 600 officers from nearly every law enforcement force in Great Britain. The inquiry team received more than 12,000 calls from members of the public and almost 11,000 hours of closed-circuit TV footage were scrutinized.

More than 100 scientists spent more than 6,000 hours analyzing “swabs” for body fluids and DNA, along with thousands of fibers from the victims themselves, including the locations where each murdered woman was found. Initially, the surface of each of the victim’s bodies was swabbed to recover foreign DNA. Over 100 swabs were taken and processed using the SGM Plus profiling method.

A DNA Match

|

| Tania Nicol |

A DNA match led police to a man named Steve Wright, who at the time of the murders was working as barman in Ipswich's red light district and as a forklift truck driver in the Ipswich Docklands. His DNA profile was held on a police computer database after a previous conviction for theft; in 2002 he was convicted of stealing £80 from a former employer. Investigators said Wright’s DNA was recovered from Anneli Alderton, Paula Clennell and Annette Nichols.

Wright was arrested at his home at 5 a.m. on December 19, 2006 and taken in for questioning. At the time, the police told the assembled media: “This is a significant arrest and the team is feeling quite buoyant.” The police said that they were no longer appealing for information in relation to the murders and that the arrest was a major breakthrough in the case. They were very certain they had the culprit – to the exclusion of all other possible suspects.

When questioned by police, Wright admitted frequently using prostitutes in Ipswich's red light district and also admitted having sex with four of the five victims but he maintained “this did not make him a murderer.”

The police also told the media that the basis of the arrest was closed-circuit TV footage which they thought showed Wright's car picking up the first victim, Tania Nicol. Wright picked her up on October 30, 2006 and her body was not found until December 8. Wright said it was “quite possible” he was the driver of the car seen in CCTV images that showed Nicol getting into a vehicle on the night of her killing but he also said that after he picked her up he changed his mind about having sex and dropped her back in Ipswich's red light district.

Steve Wright’s Background

|

| Gemma Adams |

Steve Wright had a troubled childhood and adolescence. His mother walked out on the family when he was 8 years old and he did not see her again for 25 years. He and his siblings lived with their father, who remarried and had a son and daughter with his second wife. At age 16, Wright left school with poor academic results and joined the Merchant Navy where he became a chef. While in the navy, he began to frequent prostitutes and continued to do so throughout his adult life. When he left the navy, he worked as a lorry driver, a steward on the QE2 and as a bar manager in various locations and at one point, he lived in Thailand for a few months.

He was married and divorced twice and fathered two children. His second marriage lasted only a year and he may have had a third wife in Thailand though he has always denied this.

DNA Matches Lead to Conviction

|

| Anneli Alderton |

After his arrest, initial examination of over 500 items recovered from Wright’s home and car confirmed the presence of body fluids. Scientists extracted the DNA from these fluids – using SGM Plus methods and obtained profiles matching Paula Clennell, Anneli Alderton and Annette Nichols.

Scientists also recovered fibers from the bodies of Anneli Alderton, Paula Clennell and Annette Nichols using adhesive tape. These were then compared against items recovered from Steve Wright’s home and car. There were other incriminating items uncovered such as fibers matching the carpet of Steve Wright’s car found in Tania Nicol's hair and fibers from a pair of navy blue track suit bottoms recovered from Wright’s home which were found to be “indistinguishable” from those recovered from four of the victims.

During a six week trial at Ipswich crown court, the prosecution used CCTV footage and all the forensic evidence linking Wright to the murders – links so strong that prosecution experts said the odds of being mistaken were one in a billion. In the end, jurors took only eight hours to convict Wright unanimously on all counts. In summing up, the trial judge, Mr. Justice Gross, said it was an “extremely disturbing case.”

Prosecutor Peter Wright called on the judge to impose a “whole life term.” He said the criteria for passing such a sentence were met because there was “a substantial degree of premeditation or planning.”

Wright was sentenced to life imprisonment with little chance of parole. Justice Gros called him the “epitome of evil.”

Is Steve Wright Innocent?

|

| Annette Nichols |

Wright, who adamantly professed his innocence from the time of his arrest, was shocked at his conviction. After his conviction, he said the verdict was like a “knife in the heart” as he had not expected to be found guilty. In a letter dated August of 2008 from Long Martin Prison, Worcestershire to the East Anglia Daily Times, he wrote that he was not the “real killer.” He also said that he was “numb with shock” after being found guilty of the murders and that there “was not one shred of evidence” against him.

“People should believe I am innocent because I have gone through my whole life trying to be as fair and considerate to other people as I possibly could. I don't have a violent bone in my body and to take a life I would have thought would be the ultimate form of aggression…All their evidence proved was that I had contact with the girls but not one shred of evidence showed that I killed them,” he wrote.

Wright is not alone in maintaining his innocence. To crime investigator and writer David Dixon, the forensic evidence linking Wright to the murders does not prove that Steve Wright was the killer. “The forensic experts testified that most fiber deposits would be lost in the wind and rain after a few hours of exposure to the elements, yet a full profile of Wright's DNA was found on three murder victims despite the bodies being exposed to wind and rain for several days, and even though Wright used condoms during sex with the women.”

To Dixson, all the scientific evidence only proves Wright had contact with the victims and that he had sex with four of the five murdered prostitutes – which Wright readily admitted from the outset.

Dixon says: “This CCTV footage, presented at the trial, alleged to show Tania Nicol being picked up by Wright's Ford Mondeo, but the footage was taken at night, and the car might not have been a Ford Mondeo, and if it was, it might not have been the killer's car, or Steven Wright's, and the girl getting into it may not have been Tania Nicol either.”

“Another very important point is that Paula Clennell (the final victim) reported to the police that she had seen Tania Nicol some two hours after this time, talking to a man in a silver car in the red-light district.”

|

| Paula Clennell |

Clennell therefore died as a potential material witness for Wright's defense, Dixon says. And another witness also saw Nicol talking to two men in a “posh” car after the CCTV sighting undermines this CCTV evidence completely.

Dixon believes a more obvious candidate for a suspect car is a blue BMW with polished alloy wheel hubs that was seen by several witnesses. Anneli Alderton was last seen alive getting into a dark blue BMW. Gemma Adams was last seen outside a BMW garage, according to Dixon. But this evidence never received an airing in court.

“Annette Nicholls was seen getting into a blue BMW with polished alloy wheel hubs a week before she is thought to have vanished. Tania Nicol was last seen at the driver's window talking and giggling with two men sitting in a “posh” blue car,” Dixon says.

“Another witness, a doorman at an Ipswich massage parlor, saw a driver in a blue BMW with polished alloy wheel hubs behaving very strangely in the car park in early December. The driver repeatedly reversed his car back and forth outside the door, then moved further up into the car park and did the same again, revving up his engine and stopping it repeatedly. He then drove off very fast.”

If we add up all the elements, Dixon says, what we get is “last seen alive,” “seen getting into,” “last seen outside a BMW garage,” “acting suspiciously outside a sex-related venue,” “last seen talking to two men in a posh car” – all of which must guarantee suspicion of a blue BMW.

Dixon believes Wright's defense did not make enough of this during the trial.

Wright also admitted having sex with Adams in his car at around the time she disappeared, and said that at later times he took the other women – Alderton, Clennell and Nicholls - back to his home for sex while his partner was at work. He would take them to his bedroom but would not use the bed in case his partner was able to smell sex on the bedclothes.

Instead, he had sex with them on two jackets on the floor. The court heard bloodstains from Clennell and Nicholls were found on one of the jackets.

Crown Prosecution advocate Michael Crimp said Wright was the “common denominator” linking all five murdered women. He concluded that Wright was the last person to see them alive and the scientific evidence proved he was responsible for their deaths. He said Wright had failed to give a satisfactory explanation as to why blood from two of the victims was on his jacket. This was one of the main factors in Wright's conviction.

Indeed there was no attempt by Wright's defense to investigate the origin of the blood stains. Could they have been menstrual blood? All the murdered prostitutes were drug addicts. Could this blood have been the result of lack of personal hygiene after injecting heroin? Or could the blood have resulted from rough sex with other customers earlier in the night? None of these possibilities were explored by Wright's defense in court.

According to Dixon, the prosecution also failed to explain why no jewelry and clothing from the victims had ever been found – surely if “trophies” had been kept by the murderer, they would have been uncovered in Wright's home or car.

Dixon says: “Wright made admissions that he need not have made, such as his awareness of some of the areas that the bodies were disposed in, where a dishonest denier would always deny if he could. He has had a long history of involvement with prostitutes dating back a quarter of a century with no sign of a psychopathic disposition in his history.”

Dixon also has a problem with the modus operandi of the actual murderer.

“The first two victims disappeared at fortnightly intervals and were found weeks later in a nearby river, in circumstances designed to eliminate the risk of forensic and DNA evidence. The last three were all killed in a single week, and the bodies were laid out on dry land for a quick discovery, plastered in DNA and forensic evidence that implicated the hapless defendant Steven Wright.”

Dixon says the murders can be described as “serial cascade murders” because of the change in timing between the first two murders and the last three. He believes there is also a corresponding switch between the two sets of murders, with the bodies of the first two being found in the east of Ipswich, and the bodies of the last three being found to the west of Ipswich.

Dixon concludes with the question: “Why would a serial killer accelerate the pace of his series so dramatically when the police surveillance of the small district from which he took his victims was at its height?” He may have a valid point.

Dixon is not alone in claiming the wrong man may have been convicted of the Ipswich murders.

Noel O'Gara, owner/editor of Court Publications in the Republic of Ireland has conducted his own investigation into the Ipswich murders, and last year, published an eBook about the case called The Real Suffolk Strangler. He believes the actual murderer is still on the loose.

O'Gara agrees with Dixon on a number of issues. He says: “The evidence that Steve Wright's DNA was found on the victims did not prove that he was a killer. What it did prove was that he had sexual relations with them as he admitted.”

He also agrees with Dixon that the blue car is a major “loose end” in the case, and like Dixon, he believes the existence of this car was not properly investigated by the .Ipswich police.

In his book, O'Gara suggests that a former police officer who worked as a pimp for all the murdered prostitutes was the real killer. He also claims that “the real killer” was the driver of the mysterious blue car seen in the CCTV footage shown in court.

O'Gara's chief suspect, Tom Stephens, was indeed arrested by Ipswich police before Steve Wright and was also named in one of the UK's Sunday newspapers as the potential culprit but O'Gara claims the police “lost all interest” in the ex-cop turned pimp once they arrested Steve Wright. He says Wright was a much “better fit” for the police who then stopped following leads on other suspects.

Though O'Gara spent several years gathering his own evidence in this case, he was unable to interview his chief suspect who (locals say) disappeared from the Ipswich area shortly after Wright's conviction. O'Gara says: “I went to the central police station in Ipswich to discuss my evidence but received a very hostile reception there and a request to meet the chief police officer was dismissed out of hand.”

Appeals

In March, 2008, Wright revealed he would be lodging an appeal against his conviction, as well as the trial judge's recommendation that his life sentence should mean “a whole life.” He has also claimed that the trial should never have been held in Ipswich, and that the evidence against him was not sufficient proof of his guilt. In a letter to the court of appeal, he stated: “All five women were stripped naked of clothing/jewelry/phones/bags and no evidence was found in my house or car.”

In July 2008, Wright renewed his application to appeal which was to be considered by three judges but in February 2009, he dropped this bid without explanation. British media have speculated that this decision was made because of lack of money. Wright’s family has said they hope to convince the Criminal Cases Review Commission to take on the case but they have had no success with this plan to date.

O'Gara cannot explain why Steve Wright has dropped the appeal against his conviction.

“He probably feels the cards are stacked against him. Ipswich police have repeatedly said they will not be reopening the investigation as they are satisfied they have caught the real killer.

If Steve Wright is indeed innocent, then the real killer is still on the loose.

Mystery at Tupper Lake

In solving a youth’s odd disappearance and the mystery at Tupper Lake, is dead serial killer Israel Keyes the key, or something even more nefarious?

The sprawling Adirondack mountain region of upstate New York is a dense world of water and woods. Sometimes serene, sometimes sinister, it remains a sparsely populated and unspoiled wildlife habitat, peppered with small, historic hamlets and connected by a network of mostly nameless footpaths, dirt roads, winding county routes, and, here and there, slicing through the countryside like a machete, a superhighway that seems to go on and on and on…to nowhere.

Major, minor, or backwoods, in spring, summer, autumn or winter, none of these passageways ever sees any significant amount of traffic. Not one, regardless of length or width, maintenance or neglect, is ever congested.

That peace and quiet is part of the appeal of this northern U.S. territory, for both year-round residents and the thousands of visitors who annually hike or vacation in these pristine hills during the hot, humid, and much too brief summertime.

Summer is when this tranquil place fully comes to life, when it is at its most peopled and inviting. In wintertime, though, the same idyllic landscape becomes a great deal more stark and forbidding. Deadly even, if one disrespects it.

Blizzards, howling arctic winds, and subfreezing temperatures which can grip the area for six months or more each year bring tourism to a virtual standstill then, restricting access to roads, seasonal camps and the out-of-the-way locations tourists usually like to probe, and lighting up a vacancy sign in nearly every hotel, motel and inn.

Winter and its isolation comes here early and stays late, driving away all those merely dabbling at nature, and generously returning stewardship of the mountains and lakes and beasts of the forest to the hardier full-timers.

Year after year, these rugged individuals fearlessly embrace the snow and cold, firm with the knowledge that, if they’re extra careful, they’ll surely live to feel the warmth of spring again. And that, if they aren’t, they won’t.

Vanishing into thin air

At any given time of year there are probably more dead people here than living. And, whether one believes in such things or not, countless numbers of ghosts, ancient and recent, also call the Adirondacks their home.

It’s just that kind of terrain: Haunting.

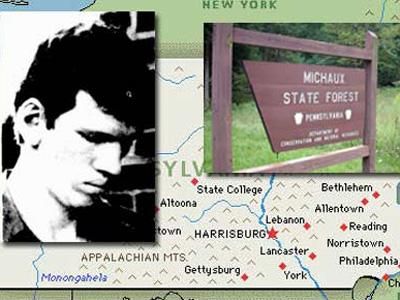

By now, although hearts are still filled with hope, there is little doubt that dwelling restlessly amongst those mountain spirits is the soul of a young man born and raised in the township of Tupper Lake named Colin Gillis. He was only 18 when he mysteriously disappeared without a trace on March 11, 2012, and no one has seen or heard from him since.

When Gillis had returned from college on Spring Break that March, the days had already begun to grow longer and warmer, although the nights, dipping down into the teens and well below, were still characteristically unforgiving.

When Gillis had returned from college on Spring Break that March, the days had already begun to grow longer and warmer, although the nights, dipping down into the teens and well below, were still characteristically unforgiving.

The pre-med student was excited to once again be in that familiar neck of the woods he “knew like the back of his hand” and was particularly looking forward to a party being held on the evening of March 10th.

There, he was planning to meet up with some of his former high school classmates, some of whom he hadn’t seen since graduation.

Gillis was dressed for a 40-degree day when he grabbed a backpack and set out for the gathering shortly after having dinner with his parents. But it was already down into the twenties and the mercury still falling when he later left that party on foot at around two in the morning, presumably intoxicated and reportedly annoyed.

The youth was last observed by a passing motorist “flailing his arms” at the side of Route 3, a desolate section of roadway between Tupper Lake proper and the village of Piercefield, where the Gillis family lives.

As it turned out, the driver of the car that passed Colin Gillis at the early morning hours of March 11th was the editor of the local paper The Lake Placid News. This trusted eyewitness happened to be ferrying his elderly mother back to her home in the village of Tupper Lake and, concerned by Gillis’ frantic conduct and for the safety of a vulnerable passenger, decided not to stop. He went instead to the nearest police station to relay the incident.

Officers from that police department have since repeatedly stated that they responded immediately to this man’s urgent-sounding report and quickly drove out to the area in question but, upon arrival, saw no one there at all. Days later, however, when a massive rescue mission was fully launched searchers came across Gillis’ driver ID card together with one of his sneakers in that exact same spot.

It’s not known therefore who it really was that last saw Colin Gillis alive. Or what.

Unsavory elements

For many thousands of years Native Americans freely traversed the domed mountain range that serves in present times as the border between Canada and the United States. Then, like now, it was a formidable and at times extremely inhospitable environment—suitable for hunting, trapping or fishing, but little else—so no one ever thought to make it a permanent residence.

The name "Adirondack" is in fact a bastardized version of the Mohawk word Ratirontaks which roughly translated means "they eat trees." The full force of that translation is somewhat lost on us today though, because it was a deeply derogatory term which the Mohawk used to describe the Algonquian-speaking tribes whom, they claimed, dined on tree buds and bark whenever better food became scarce.

Fate has been unkind to all Native American peoples, so it is therefore impossible now to verify either the superiority of the Mohawk way of life or the Algonquians lowliness. But the historical grudges and insults of one tribe lobbed against the other are probably best dismissed as amounting to nothing more than ordinary cultural bias, such as has plagued every civilization since the beginning of time.

Still, the Adirondack Mountains are not, by virtue of their majestic stature, somehow exempt from having an actual lowlife element crouching in their shadows, and the record shows that some of these individuals have been far more onerous than the tree-eating variety.

A lake and a lair

In the northernmost tip of the Adirondack mountain region there sits a rundown cabin on a fairly modest-sized piece of property consisting mainly of old growth forest, towering pines, and swampland.

A ramshackle abode nestled within the darkest recesses of upstate New York, it was of little or no interest to anyone for all the years that its mostly-absent owner had quietly paid the taxes on it. But recently this rustic hideaway has become the subject of much speculation and mad searches.

Here, from 1997 to 2012, the now-dead serial killer Israel Keyes had set up his home-away-from-home for whenever he was on the east coast and prowling. Here, the FBI continues to diligently hunt for clues as to the identities and locations of his many unknown victims. Here, police dig intermittently for bodies and bones.

Although Keyes killed himself in an Alaskan jail cell before officials could fully extract all the details of his heinous crimes, based on those he did confess to, he is believed to have been one of the most mobile and possibly most prolific serial slayers known to date.

Moreover, he had been operating throughout the entire country for approximately a decade without his neighbors, family, friends, wife, or daughter ever suspecting he had such a lethal hobby.

Burying “kill kits” all over America. Plotting murders months and even years in advance. Traveling hundreds, sometimes thousands, of miles to snatch a victim. Robbing banks along the way. Burning buildings. Raping. Torturing. Dismembering. Keyes was certainly one of the most methodical, heartless, and criminally insane of all serial murdering sociopaths.

An exceptionally depraved man who enjoyed every aspect of doing wrong, except getting caught for it.

By 2009, when Keyes decided to rob a bank in the small but quaint Adirondack village of Tupper Lake New York, he was already descending into uncontrollable madness: breaking his own rules in targeting a town so close to his own turf, and taking more and more unwarranted risks to accomplish his numerous other misdeeds.

That was an inevitable decline, experts say. Even the most “organized” breed of killer, like Keyes was, will someday fall prey to their own psychosis and start compulsively offending until they finally get nabbed. And although Keyes was never pursued or fingered for the Tupper Lake heist, it wasn’t very long after committing this rash act that he was apprehended.

March 13th, 2012, to be exact.

Road kill

Stalker, thief, kidnapper, rapist, torturer, arsonist…Israel Keyes was a deadly and sadistic predator. A former U.S. soldier, he skillfully and opportunistically hunted in public parks, boatyards, campgrounds, cemeteries, or highways, abducting and slaying the young or the old, males or females—whomever struck his fancy—sometimes pairs of them.

It is understandable why evil men like that are often rumored to have supernatural powers aiding them, but it’s unlikely that even this demonically possessed killer could have been in two places at one time. Not at the height of his crime spree, nor in March of 2012 when it was abruptly brought to an end.

Yet this is what some spooked citizens of Tupper Lake, on learning it was Keyes who pulled off the 2009 bank job there, now believe.

They suspect he was not really in Texas in March of 2012, as authorities claimed, but, rather, driving along Route 3 to his secret shack at the very moment that Colin Gillis was stumbling homeward.

They think that Keyes then stopped to offer the cold, befuddled and unsuspecting youngster a ride, and at some point he killed the boy, chopped him into bits and pieces as he’d done to all his other victims, and then scattered the remains where they’ll never be found again.

And to defeat those cruel ends the Gillis family has posted a $25,000 reward.

End of the road for wanderlust killings

Agents from the FBI are dead certain that Israel Keyes’ last and final victim was 18-year-old Samantha Koenig, who, on February 1, 2012, he’d abducted at gunpoint from an Alaskan drive-through coffee stand, transported in bondage to a shed at his residence, raped, tortured, and strangled.

Agents from the FBI are dead certain that Israel Keyes’ last and final victim was 18-year-old Samantha Koenig, who, on February 1, 2012, he’d abducted at gunpoint from an Alaskan drive-through coffee stand, transported in bondage to a shed at his residence, raped, tortured, and strangled.

After that, a giddy Keyes took a mini-vacation in New Orleans to celebrate the heartless crime, using his victim’s ATM card to finance the excursion with, until, eventually, her limited funds ran out and he was forced to go back home again.

When he returned, he dumped Koenig’s dismembered body in a semi-frozen lake close by, but, before mutilating it, snapped a lifelike-looking photo in order to deceive the girl’s distraught family into replenishing her drained debit card with a $30,000 ransom.

The fact that the teen’s banking account remained active throughout her inexplicable absence, also gave her loved ones false hope they would see her alive again.

At roughly 1:30 a.m. on March 11th, when 18-year-old Colin Gillis also uncharacteristically went missing, killer Keyes was once more in travel mode, but this time journeying the Texas highways, the FBI insists, although still using Koenig’s debit card to illicitly finance his trip. A trail of ATM withdrawals he left like breadcrumbs across the Lone Star state would also seem to confirm the killer’s whereabouts on that morning.

Two days later, however, on March 13th, wayward Keyes’ whirlwind would end abruptly in his arrest by a trooper who pulled him over for a traffic violation and recognized he was the “person of interest” being sought in the abduction of a pretty “Alaskan barista” from Anchorage.

There were shreds of withdrawal receipts from her account strewn on the passenger seat of his car, a stack of ransom cash at his fingertips, a murderer’s arsenal stored in his trunk, and a dark confession on the tip of his tongue.

At this point in time though, nobody knew yet that the young lady was in fact slain. Nobody knew yet of this man’s taste for blood. Nobody knew yet that Colin Gillis would never be seen again…

Gillis is described as a Caucasian male, approximately six-foot tall and 180 pounds, with light hair and blue eyes. He was a second-year pre-med student at the State University of New York at Brockport when he vanished.

Did a group of partygoers he’s alleged to have quarreled with before leaving on foot that day seek him out for revenge? Did the police successfully intercept him instead and, in the process, cause his death by applying excessive force while attempting to make an arrest? Did a pack of hungry wolves stalk the youth as he was obliviously walking the remote road in darkness and then drag his body into the woods to devour it?

Or did an infamous roaming serial killer, sensing capture was imminent, elude the Texan posse so to visit his New York hideout for one last time, and on the way seized upon a convenient kill?

This has become the number one mystery at Tupper Lake now, which the Gillis family desperately hopes to solve someday.

True crime writer Eponymous Rox is the author of THE CASE OF THE DROWNING MEN and HUNTING SMILEY. You can learn more about Colin Gillis and follow developments in his missing person case—as well as others like it—at the Killing Killers website. Visit the 'Find Colin Gillis' Facebook page here.

The War Hero Who Became a Child Rapist

April 29, 2013

Screenshot from the motion picture Black Hawk Down

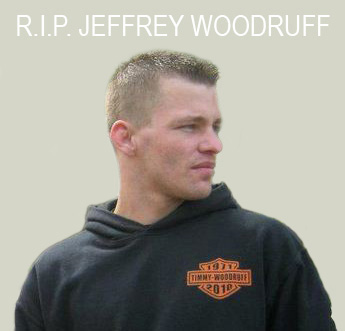

Specialist 4 John “Stebby” Stebbins won the Silver Star for his heroics at the Battle of Mogadishu in 1993. Since 2000 he’s been serving a 30-year sentence for raping his 6-year-old daughter.

by David Robb

You may have seen the movie Black Hawk Down. It was one of the biggest box office hits of 2001, and earned its director an Oscar nomination. The film, based on Mark Bowden’s nonfiction book of the same name, told the story of the 1993 Battle of Mogadishu. One of the real life Army heroes of the battle was Specialist 4 John ‘Stebby’ Stebbins, who was shot three different times – and thought dead each time – but recovered from his wounds and received the Silver Star, the third-highest military honor.

A former baker from upstate New York, Stebbins served as the company clerk for an elite unit of Army Rangers. His fellow soldiers referred to him as “chief coffee maker” and “paper pusher.” But when thrown into battle, his heroics surprised everyone.

“He was a changed man, a wild animal, dancing around, shooting like a madman,” Bowden wrote in his book.

In the movie, all the combatants are depicted under their real names – everyone, that is, but Stebbins. The Army insisted that his name be changed in the movie because the year before its release, he was convicted in a military court martial of raping his own 6-year-old daughter.

The transcript of the court-martial reveals that around October 1, 1998, when Stebbins and his family lived at Fort Benning, Georgia, “he began sexually abusing his 6-year-old daughter” – who is identified in the court record as “MS.”

“(He) approached MS and asked her whether she had seen him in bed with his wife. After she replied that she had, (he) made MS remove her clothes, lie face down on the bed and spread her legs. He then raped her. (He) admits that he raped MS at least two more times before September 30, 1999. Before raping MS for a third time, (he) also forcibly sodomized her.

“(His) offenses were discovered on March 17, 1999, after (he) and his wife separated and were living apart. In response to an argument, (he) and his wife had over the telephone, MS, who was then 7, told her mother that she was “mad at him” and that she “hated him…because he did sex to me.” When questioned by her mother, MS indicated that (her father) had penetrated her genitals and anus and had placed his penis in her mouth.”

This was not the kind of hero the Army wanted portrayed in Black Hawk Down. So in exchange for receiving Pentagon permission to use actual Army Black Hawks in the movie, the producers agreed to change the name of his character. The real life John Stebbins became the fictional “John Grimes,” the only fictional character in the movie. And so Stebbins was written out of the script – literally.

The real John Stebbins is currently serving a 30-year sentence at the Fort Leavenworth military prison in Kansas.

Jesse James: The Baddest Outlaw of Them All

May 2, 2013

“Surrender had played out for good with me…” Jesse James.

When the Ford brothers assassinated Jesse James on April 3, 1882, the longest-running outlaw saga in American history was over.

by Robert Walsh

Confederate bushwhacker, desperate outlaw, bank robber, political terrorist, gang leader, multiple murderer, folk hero. Jesse James was all of them. One thing he wasn’t (as much as his latter-day apologists like John Newman Edwards would like you to think) was some sort of Robin Hood who stole from the rich and gave to the poor. While he made great play of continuing to fight for the Confederate cause (when he wasn’t claiming to represent poor, dispossessed Missourians against rich Northern carpetbaggers) he was out for himself.

There was certainly an element of political thought behind his actions (Northern banks and businesses often being prime targets) but most of what he stole stayed in his pocket and, while violence was always going to be a part of his life and career, he also killed even when there was no need for bloodshed.

To understand Jesse James one needs to understand the context into which he was born. Jesse was born in Clay County, Missouri in 1847. Clay County was by far the most pro-Southern county in Missouri, its people and its ways having earned it the nickname “Little Dixie.”

The Kansas-Missouri Border Wars erupted around the issue of slavery and emancipation during the 1850s. Missourians could keep slaves (the James family themselves owned a few) while Kansas outlawed slavery. Even in the 1850s, years before the Civil War began in 1861, pro-and-anti-slavery groups organized themselves into armed bands, raiding and fighting long before the Confederacy even existed. Jesse grew up amid a climate of political violence where the bullet often outweighed the ballot box. Guerilla groups such as the pro-Southern “Bushwhackers” and pro-Northern “Jayhawkers” and the largely-criminal “Redlegs” (named for the red gaiters they wore) routinely fought running battles during the period now known as “Bleeding Kansas.”

When the Civil War began, Jesse wasn’t old enough at first to join the Bushwhackers he so admired. His older brother Frank began riding with infamous Confederate William Quantrill (leader of “Quantrill’s Raiders”) but Quantrill turned Jesse down, stating that 16 years old was simply too young. A few months later rival Confederate William “Bloody Bill” Anderson wasn’t so fussy. Jesse had found himself a particularly unpleasant mentor.

Bloody Bill was well named. He hated Yankees with such passion that he collected the scalps of his victims during raids and skirmishes. He was brutal, fanatical, and utterly indifferent to killing anyone who opposed him and, while the perfect mentor for a wannabe guerilla, he couldn’t have been any worse for an impressionable teenager already noted by Anderson and others as a more-than-capable fighter. Jesse having been born into violence and death, Anderson’s influence could only have been deeply negative.

Atrocities were common on both sides. Bushwhackers, Jayhawkers and Redlegs routinely conducted reprisals against each other and, seeing as there were increasingly few official Confederate troops in Missouri, reprisals by Jayhawkers were often against civilians they believed had ties to known or suspected Bushwhackers. The infamous Redlegs were nominally pro-Union, but in practice they tended towards preying on innocent civilians as much as Confederate sympathizers.

The James family was not exempt from reprisals. Jesse was still living on the family farm near Kearney – not far from St. Joseph, Missouri – when Jayhawkers arrived. They beat Jesse and tortured his stepfather Joseph, suspecting rightly that they were well aware of Frank’s activities with Quantrill. Despite Jesse being severely beaten and his stepfather partially hanged, neither gave anything away. Perhaps not surprisingly, Jesse too now held a lasting grudge against pro-Northern forces and it was then that he sought out Anderson and joined his band of Bushwhackers.

Guerilla Wars: Raiding as a Way of Life

The guerilla war conducted in Missouri was especially personal. In Missouri almost everybody knew everybody else’s affiliations and so former friends and even family members often found themselves on opposite sides, making the fighting especially personal and especially vicious. Frank took an active role in the notorious”Lawrence Massacre” in 1863, where Union troops and pro-Union civilians were killed en masse while Jesse was involved in the equally notorious “Centralia Massacre” in 1864, where captured Union troops and civilians aboard a hijacked train were beaten, shot and, in some cases, scalped.

By late 1864official Confederate forces had withdrawn from Missouri. Frank was still riding with Quantrill and Jesse was firmly established with Anderson, at least until Anderson’s death after being ambushed by Union cavalry. Anderson’s death made Jesse’s grudge even deeper. He swore vengeance.

Towards the end of the Civil War, Jesse also suffered the second of two life-threatening war wounds when he was shot through the lung by a Union cavalryman. The fact that he was actually trying to surrender doubtless did little to cool his grudge.

Life as a Bushwhacker was perfect training for aspiring outlaws. By the end of the war, Jesse was well-used to life spent perpetually on the run, always outnumbered, outgunned, headed straight from one fight into another and he became fully accustomed to raiding as a lifestyle, killing as a regular event and the possibility of dying being an occupational hazard. His being several years younger than Frank probably accounts for his more aggressive, hot-headed nature, making him more likely to start shooting when Frank might have acted differently in the same situations. Anderson’s malign influence at such a young age, coupled with Jesse having been born into a violent time and place, suggests that his becoming a full-time outlaw was predictable.

Reconstruction in Missouri

With the defeat of the Confederates in 1865, the James boys were forced into an oppressive way of life. Being former Bushwhackers they couldn’t vote, own property, run their own businesses or even preach in their own local churches and, perhaps most galling of all, were forced to swear an oath of allegiance to the Union. Part of Reconstruction in Missouri involved repressing former Confederate fighters and their sympathizers and the increasing dominance of Northern “carpetbaggers” who began sweepingaway old ideas and reshaping Missouri in the Northern image. The carpetbaggers began steadily pushing out long-held traditions, dominating commerce and business in the enforced absence of locals who ran things before the war and were often barred from doing so afterward for their Confederate sympathies. The pre-war way of life was being squeezed out of existence at the expense of many native Missourians and their former Northern enemies were squeezing by any means available.

Jesse chafed at such restrictions. Being made to feel like a second-class citizen in his own land was bad enough, but watching his old way of life destroyed to benefit outsiders (especially Northerners) was endlessly provocative to him. Between the Confederate surrender in April, 1865 and the start of Jesse’s outlaw career in 1866, the restrictions on former rebels and increasing dominance by Northern interests fuelled his resentment, stoking (so he always claimed) his desire to keep fighting for a cause already lost.

The James-Younger Gang

With these factors in mind, Jesse began recruiting former Bushwhackers into a fully fledged outlaw gang. First on his list was older brother Frank. After Frank, the James brothers recruited two of Frank’s fellow Quantrill Raiders, Bob and Cole Younger. Bob and Cole enlisted their brother Jim and once the gang heard of former “Bloody Bill”Anderson associate Arch Clements (an acquaintance of Jesse’s already running his own gang, fighting Union troops and conducting a series of armed robberies) they opted to ride with Clements. Other members came and went (Bill Chadwell, Clell Miller, Charlie Pitts, Bob and Charlie Ford among others), but the James and Younger brothers were always the nucleus around what became known as the “James-Younger Gang.”

After the death of Clements while fighting Union cavalry, the gang was led by Jesse, with the experienced, cooler heads of Frank James and Cole Younger an essential part of planning raids and ensuring the gang’s survival. Jesse also had a novel new target for armed robberies: banks. Outlaws of the day usually robbed trains and stagecoaches for payrolls and whatever they could take from passengers as banks were deemed too well protected, despite their undoubted assets. Indeed, the very first American bank robbery occurred during the Civil War when a man named Green earned himself $5,000 (and a hangman’s noose) after robbing a Massachusetts bank, murdering a cashier in the process. Before Jesse, banks were considered off-limits, after Jesse (and even today) they’re considered fair game.

It’s said that Jesse took a particular interest in banks because many banks were owned by rich Northern carpetbaggers or at least funded the carpetbaggers as they “reconstructed” the old South according to Northern ways and ideas. They seemed an especially attractive way to strike directly against Jesse’s old enemy even after the Civil War had ended. Setting aside the political statement of robbing banks, Jesse liked the large amounts of ready cash robbing banks provided.

The First Peacetime Daylight Bank Robbery in U.S. History

The first bank robbed by members of the James Gang was in Liberty, Missouri in early 1866. The target was the Clay County Savings Association (familiar turf for the James and Younger boys). It was the first peacetime, daylight bank robbery in American history and the bank had been funded by anti-slavery Republicans which possiblymade it especially appealing. There’s no firm evidence to confirm that either Jesse or Frank took part (eyewitness reports are conflicting and no physical evidence exists either) but what is widely believed is that the James brothers were at least involved in the planning, if not necessarily the robbery itself. A bystander, a student at William Jewell College (which, ironically, Jesse’s father helped found) was shot dead as the robbers escaped with nearly $4,000 in banknotes and gold.

The James-Younger Gang was firmly on its way and there was no turning back. The gang made the leap from Confederate guerillas to full-time outlaws who could expect long sentences at best and at worst either a professional hangman or a lynch mob. Fortunately for them, Clay County folk retained much sympathy for the defeated South and, being rural folk, were used to keeping local secrets from outsiders, especially Northerners. Even though many local people must have had at least some idea who the robbers were, nobody said anything and nobody was likely to either.

Oddly, for a supposedly pro-Confederate gang still clinging to the Southern cause, many of their robberies were of small local banks containing local money rather than that of the hated carpetbaggers. This being a time before bank robberies were insured by the Federal Government, robbing local banks was only likely to hurt local people and businesses which contradicts the myth of Jesse’s band being entirely politically motivated. Despite the Robin Hood myth so ably peddled by the gang’s apologists and supporters, especially journalist (and unofficial public relations wizard for the gang) John Newman Edwards, very little stolen money found its way from the banks of the rich into the pockets of the poor. Jesse might have believed that he was acting to represent the downtrodden Missourians and the defeated Confederacy (so might Edwards for that matter) but I’ve no doubt that Jesse fully understood the value of providing some kind of justification for his many crimes and that Edwards probably recognized the value of a widely read, long-running syndicated saga when he saw one.